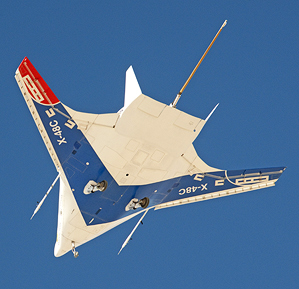

Aerospace engineers have long known that ditching a conventional tubular fuselage in favor of a manta-ray-like “hybrid wing” shape could dramatically reduce fuel consumption. A team at NASA has now demonstrated a manufacturing method that promises to make the design practical. Combined with an extremely efficient type of engine, called an ultra-high bypass ratio engine, the hybrid wing design could use half as much fuel as conventional aircraft. Although it may take 20 years for the technology to come to market, the manufacturing method developed at NASA could help improve conventional commercial aircraft within the next eight to 10 years, estimates Fay Collier, a NASA program manager. The manufacturing technique lowers the weight of structural components of an aircraft by 25 percent, which could significantly reduce fuel consumption. The advances are the culmination of a three-year, $300 million effort by NASA and partners including Pratt & Whitney and Boeing. There are two key challenges with the flying wing design. One is how to control such a plane at low speeds. NASA previously addressed this by building a six-meter-wide remote-controlled test aircraft (the X-48B) to demonstrate ways to control hybrid wings. Based on those tests and wind tunnel tests, NASA built a larger remote-controlled aircraft that started test flights last year. The second challenge is building a full-scale version of the aircraft with pressurized cabins that is structurally sound. One reason tubular airplanes have persisted is that it’s relatively easy to build a tube that can withstand the forces acting on it from the outside during flight while maintaining cabin pressure. The hybrid wing design involves a flatter, box-like fuselage that blends with the wings. The flatter structure, which includes some near-right angles, is much more difficult to build in a way that’s strong enough and light enough to be practical. NASA’s manufacturing process starts with preformed carbon composite rods. The rods are covered with carbon fiber fabric and stitched into place. Fabric is then stitched over foam strips to create cross members. The fabric is impregnated with an epoxy to create a rigid composite structure.

Sections of a fuselage built with the technique were tested and shown to withstand up to the forces that would be applied to a finished aircraft. Tests also showed that when enough pressure was applied to cause the parts to fail, the stitching used to make the structure stopped cracks from spreading—a key to avoiding catastrophic failure in flight. The researchers are now building a 30-foot-wide, two-level pressurized structure that will be used in an attempt to validate the manufacturing approach. That structure is scheduled to be finished by 2015. To achieve a 50 percent reduction in fuel consumption, the hybrid wing design will need to incorporate an advanced engine design. Collier says ultra-high bypass engines are a good match. In an ultra-high bypass design, the front fan on the engine is far larger than the core of the engine, where air is compressed and combustion takes place. Such large fans can be difficult to mount under the wing, as engines are mounted in most conventional airliners. The hybrid wing design involves mounting the engines on top of the plane, rather than under the wings (The top-mount design also cuts noise levels.) NASA has helped Pratt & Whitney develop prototype ultra-high bypass engines, which are slated to go into commercial use for the first time next year, starting on Bombardier’s C-Series aircraft. NASA is further optimizing the engines to take advantage of the top-mount design in the hybrid wing airplane.